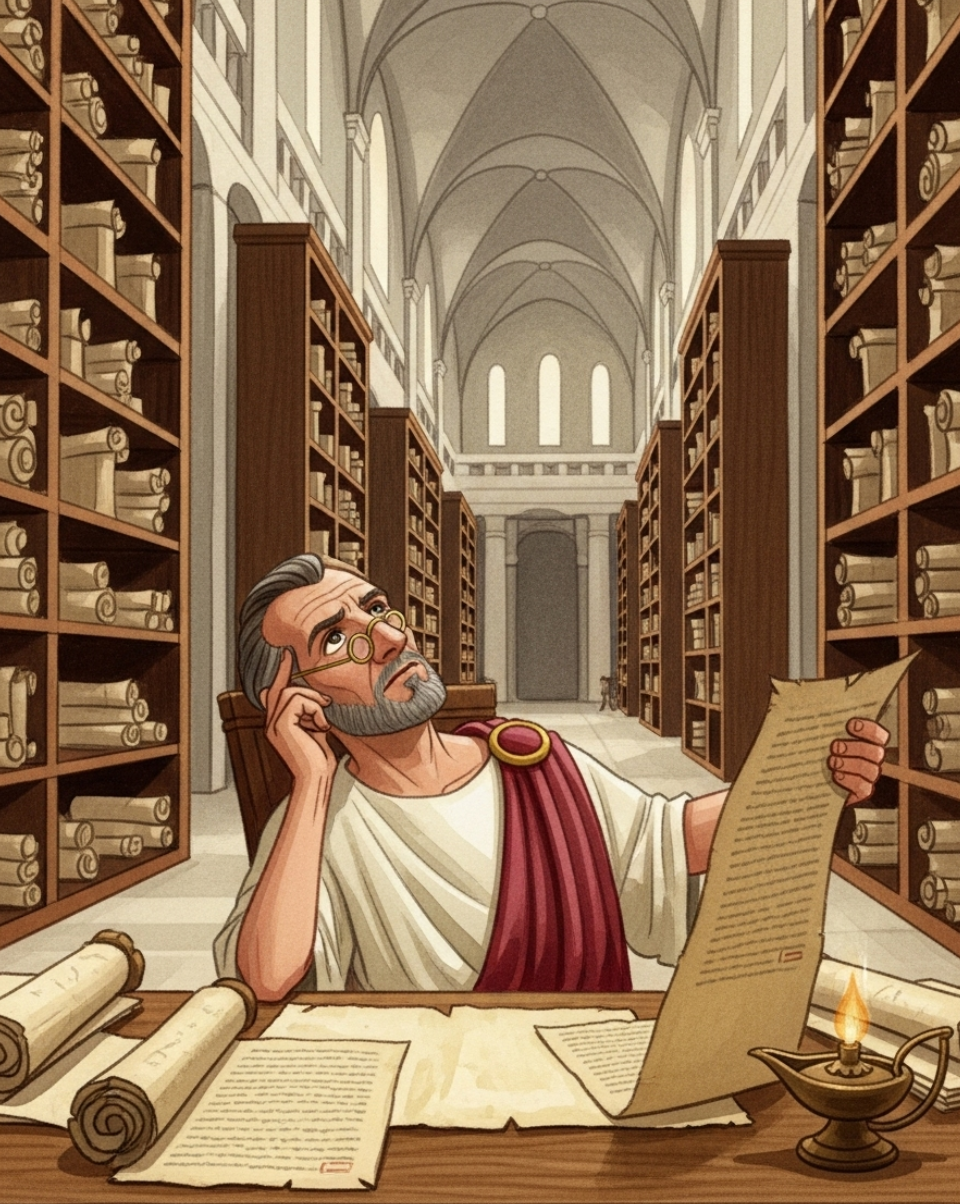

The air in the Great Library of Alexandria was thick with the scent of papyrus and incense.

Apollonius of Rhodes, the esteemed head librarian, adjusted his spectacles, the weight of the freshly acquired Septuagint a tangible presence in his hands. He’d heard the whispers, the outlandish claims: “The Eighth Wonder of the World!”

He scoffed internally. Wonders, in his experience, were carved from stone, elevated by human ingenuity, or illuminated by fire — the colossal Lighthouse of Pharos, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon, the very pyramids of his homeland…

How could a collection of religious texts, even one apparently meticulously translated into Greek, stand alongside such awe-inspiring feats? It was, he believed, a testament to the credulity of zealots, nothing more.

He began to read, driven by a scholarly duty to examine all available knowledge, no matter how fantastical.

The opening accounts of demi-gods,” the Nephilim” caused him to frown. They were reminiscent of the heroic myths of Greece, where gods mingled freely with mortals, siring offspring that were often more trouble than they were worth. Yet, the Septuagint’s depiction of these beings, their wickedness leading to the great judgment, felt less like fanciful embellishment and more like a dire cautionary tale, perhaps a historical memory distorted by time but rooted in actual events.

Then came the worldwide flood, which equally pricked his academic interest. It resonated with fragmented tales he’d encountered from Sumerian and Babylonian tablets, though those often featured squabbling, capricious deities. Here, a singular, powerful force orchestrated the event, and the narrative, surprisingly, possessed a stark, compelling logic.

Then there was the start of Babylon. At Babel, where the languages were confused. It was a different take on the reason behind the variety of languages he had encountered.

Again it was a simple, even elegant explanation of things that appealed to his rational mind. However he dismissed this as skillful story telling.

However his brow furrowed deeper as he read the story of Joseph. The details of the seven years of plenty followed by seven years of famine, the shrewd governance, the centralisation of power in Egypt under Joseph’s hand – it began to align with snippets from his own chronicles of Egyptian history, the vague mentions of periods of great abundance preceding times of severe hardship. Could this Joseph, this outsider, have been the architect of such an unparalleled survival? The account painted a picture of administrative brilliance, a foresight that dwarfed even the most cunning of pharaonic advisors.

And then, the Jews. Their story, from their humble beginnings to their growth into a multitude within Egypt, stirred something within him. He had, of course, read Egyptian records, seen the occasional cryptic references to a troublesome, numerous people dwelling in Goshen. But the Septuagint offered an internal perspective, a detailed, often harrowing, narrative of their bondage.

The Exodus. He found himself gripping the scroll tighter. The plagues, the divine interventions, the dramatic crossing of the “Red Sea”. He recalled faint, almost dismissive, Egyptian legends of a pharaoh who had suffered a calamitous defeat, whose mind had supposedly unravelled in the aftermath of a pursuit into impassable marshlands. The Septuagint provided a chillingly plausible explanation for those vague and often downplayed accounts. A pharaoh, driven to madness not by divine wrath, but by the sheer, inexplicable vanishing of his elite army? It made more sense than a mere natural disaster, especially if it was accompanied by such overt defiance of Egyptian gods.

The laws, too, captivated him. Unlike the often arbitrary decrees of pharaonic rule, these laws, seemingly handed down from a singular, transcendent deity, were comprehensive, just, and permeated every aspect of life – from ritual purity to civil justice, even to the ethical treatment of servants and strangers. It was a level of societal organization and moral conviction he had rarely, if ever, seen prescribed with such unwavering authority.

He leaned back, the papyrus unrolled across his desk, the lamp casting long shadows. His meticulously catalogued knowledge of Egyptian theology, with its pantheon of animal-headed gods, its intricate rituals, its cyclical myths of death and rebirth, suddenly felt… less substantial. Less true.

Maybe the stories in the Septuagint were not mere fables or allegories. Maybe they were history, recorded with more precision than the usual religious texts, and with an underlying coherence that his own fragmented histories often lacked. The characters, the events, the very progression of human and divine interaction, seemed to fit, to explain, to provide a missing thread in the tapestry of the ancient world.

He looked at the small, carved idol of Thoth on his desk, the god of wisdom and writing. Its impassive, ibis-headed gaze seemed to mock him, or perhaps, to silently challenge him. For centuries, he and his predecessors had meticulously collected, preserved, and studied the wisdom of the world. Yet, this “religious textbook,” dismissed at first as a curious anomaly, had unearthed a profound truth that shook the very foundations of his understanding.

The “Eighth Wonder of the World”? He closed his eyes, the narratives swirling in his mind. If these stories were true, if this singular God truly governed the cosmos, what then of Osiris, Isis, Ra, and the Mighty Nile? What then of all he had ever believed?

Check out the illustrated /audio version of this story:

Leave a Reply to GWT Cancel reply